Snap Insight: Jetstar Asia closure - the writing was on the wall

SINGAPORE: The decision for Jetstar Asia to close shop in Singapore on Jul 31 was not entirely a surprise. The writing was on the wall: The low-cost carrier has been largely loss-making throughout its existence, only profitable for six of its 20 years. This year, it expects to lose A$35 million (US$22.8 million).

Still, the news on Wednesday (Jun 11) came as a shock, due to over 500 employees losing their jobs as well as the suddenness of its exit. It had added a new destination, Labuan Bajo, as recently as March.

The Jetstar Asia business model has been described as the “airline-within-airline” strategy. It is 49 per cent owned by Australia’s national carrier Qantas and 51 per cent by Singapore company Westbrook Investments, with links to a local tour agency.

It was first introduced in the United States in 2003, when United Airlines formed Ted to fend off budget competitors such as JetBlue and Frontier. Five years later, United was forced to shutter Ted due to higher jet fuel prices.

Jetstar Asia’s demise is different, people close to Qantas told me.

This strategy is not uncommon in the industry: think Singapore Airlines and Scoot, or Lufthansa and German Wings. Less common though, was Qantas’ decision to base Jetstar Asia in Singapore in a bid to focus on this regional market, separate from Jetstar Airways in Australia.

BUDGET AIRLINES MUST BE RUTHLESSLY COST-EFFICIENT

The main reasons for closure, these observers argued, stemmed from changes in the dynamics at Changi Airport and the high cost of being based in Singapore when low-cost carriers have to be ruthlessly cost-efficient.

First, the rise in the Singapore dollar versus the Australian dollar has put tremendous strain on Qantas. In the past six months, the SGD has appreciated by more than 2 per cent against the AUD.

Second, some Jetstar Asia officials felt it was hard done by when it was forced to move from Terminal 1 at Changi (where Qantas flies into and thus allowing for seamless connectivity) to Terminal 4, the budget terminal.

This meant inconvenience for passengers connecting between Jetstar Asia flights and Qantas and other major airlines. The budget terminal is the only one without a Skytrain connection to the three main terminals, although landside and airside buses are available.

The terminal change was publicly opposed by the airline when it was announced in July 2022 and only took place in March 2023, after months of negotiation.

In recent times Jetstar Asia’s shareholders were also said to be concerned over Changi Airport Group’s introduction of new levies for passengers and airlines alike, due to higher running costs there.

LOW-COST JUST IN NAME?

The immediate implications to operations at Changi Airport, fortunately, are not severe given that Jetstar Asia makes up less than 5 per cent of all flights at the airport.

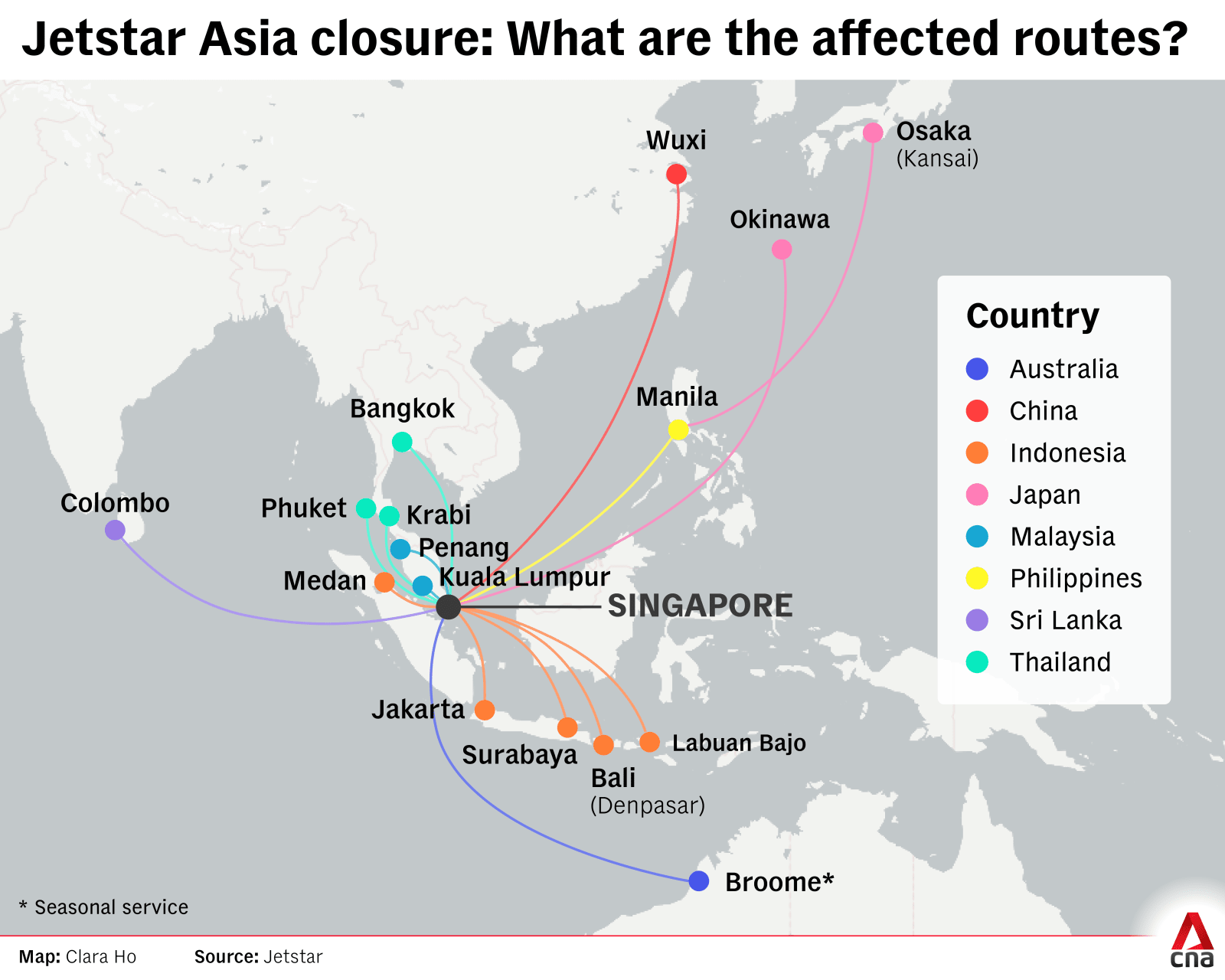

The shutdown will however create a new vacuum for 16 intra-Asia routes once plied by the airline, likely to be mopped up by the likes of Malaysia’s AirAsia and Indonesia’s Lion Air Group.

Trade associations such as the International Air Transport Association (IATA) and the Association of Asia Pacific Airlines (AAPA) remain positive on the outlook for airlines this year.

While no other low-cost carriers in the region are expected to close down, several, like Vietjet, face financial constraints and have been unable to completely shrug off structural issues brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Budget airlines may soon run into the problem of being low-cost just in name. Higher operating and ancillary costs, amid increased competition and uncertainty linked to the wider global economy, mean the gap is narrowing between legacy airlines and low-cost carriers in the short- to medium-haul sector.

Shukor Yusof is the founder of Endau Analytics, an independent aviation advisory firm based in Singapore.

免責聲明:投資有風險,本文並非投資建議,以上內容不應被視為任何金融產品的購買或出售要約、建議或邀請,作者或其他用戶的任何相關討論、評論或帖子也不應被視為此類內容。本文僅供一般參考,不考慮您的個人投資目標、財務狀況或需求。TTM對信息的準確性和完整性不承擔任何責任或保證,投資者應自行研究並在投資前尋求專業建議。

熱議股票

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10