What's behind Indonesia’s US$25 billion plan to help villagers and why are experts concerned?

JAKARTA: From loans for underbanked farmers to distributing subsidised goods and food aid to poor families, millions of rural Indonesians’ woes could be solved by a newly launched initiative, according to officials.

These Red-White cooperatives, named after the colours of the country’s national flag, will not only distribute goods subsidised by the government, like cooking oil and fertilisers, but also offer a wide range of services.

While its intentions might be noble, the initiative - which comes with a 400 trillion rupiah (US$25 billion) price tag – could pose serious risks to the economy if not executed properly, analysts said.

They warned that the programme could suffer the same fate as a failed Suharto-era policy, which was riddled with mismanagement and corruption practices. Based on the number of cooperatives set up, current President Prabowo Subianto’s programme is nine times bigger than the country’s second president’s.

Due to the sheer scale of the newly-launched programme and the way these cooperatives are financed, experts said Prabowo’s initiative could also leave some villages trapped in a cycle of debt while state-owned banks risk having liquidity issues.

“Many cooperatives are not professionally managed and eventually collapsed because of mismanagement, mounting debt and corruption,” Achmad Nur Hidayat, an economics and public policy lecturer from the Jakarta National Development University, told CNA.

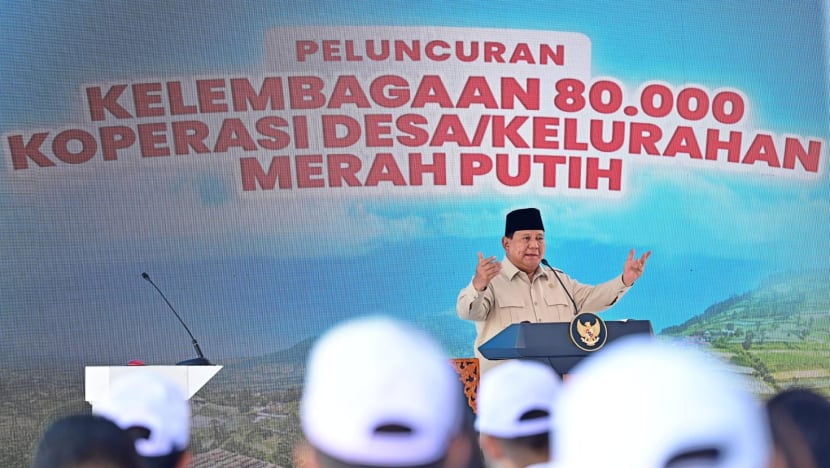

Speaking at a launch ceremony for the cooperatives in Central Java on Monday (Jul 21), Prabowo said more than 80,000 of these cooperatives will operate across Indonesia over the next three months, adding that 108 are currently operational.

"Each village will have a warehouse to store (people's) harvests. We will also have shops for basic necessities, along with savings and loans services,” Prabowo said.

Each cooperative will also operate a small clinic and a pharmacy as well as offer transportation solutions for farmers looking to bring their goods to nearby markets, he added.

HOW ARE THE COOPERATIVES FINANCED?

In launching the cooperatives, Prabowo sought to explain why his government did so with a big bang.

He said the cooperatives will provide rice milling services so farmers no longer need to sell their grains for cheap to private millers.

Prabowo argued that there have been many cases where subsidised fertilisers ended up in the hands of brokers who resold them to farmers with huge mark-ups. There were also times when farmers had to borrow money from loan sharks because a family member fell ill.

“These (areas) are what we must address and we are addressing them with big steps,” he said, explaining why the cooperatives were launched at such a scale and in less than five months since the idea was floated in early March.

“We are a big nation, so we have to think big and have the guts to take big actions.”

The cooperatives initiative is just one of a series of ambitious programmes spearheaded by Prabowo since he took office in October.

In January, the president launched his signature free meal initiative, which aims to feed 83 million children, pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers with one free meal a day. Prabowo also plans to build three million houses for low-income families annually and establish 100 boarding schools for the poor every year.

On Jul 1, the Finance Ministry predicted all of these programmes would cause a government deficit of around US$40 billion, or 2.7 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) by the end of 2025.

Not wanting to cause further deficit, Indonesian officials decided to partially finance these cooperatives by reallocating money meant for the village fund programme, an initiative meant to support small-scale infrastructure and economic empowerment projects, which Prabowo’s predecessor, Joko Widodo, initiated in 2015.

Prabowo has said that the village fund programme “does not bring the needed changes” and that money for the legacy programme should be redirected to his village cooperative initiative instead.

But Zulkifli Hasan, coordinating minister for food affairs and chief of a government task force in charge of the Red-White cooperative project, said money from the village fund programme would cover only part of the initial capital needed to set up a single cooperative.

Each cooperative must then apply for loans of up to 3 billion rupiah from state-owned banks to develop the many business arms these cooperatives are expected to have.

Banks will scrutinise the loan applications so that they can reduce the risk of default.

“(Cooperatives) will have to state how they plan to use the money, when they expect to be profitable and so on. So we are (giving loans) the right way, not the easy way,” he said at the programme’s launch.

Experts however warn that loan defaults among the newly built cooperatives will be high.

“It’s a preposterous financing scheme,” Media Askar, a researcher from Jakarta-based think-tank Center for Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), told CNA.

For one, he said that state-owned lenders might not have enough money to lend to all 80,000 cooperatives.

Indonesia’s biggest state-owned lender, Bank Mandiri, for example, manages an asset of 2,400 trillion rupiah for 30.7 million customers while its smallest, Bank Syariah Indonesia, oversees 400 trillion rupiah for 19 million account holders.

“The banks’ assets would be reduced to zero just by lending billions of rupiah to thousands of cooperatives,” Media said.

“And these (cooperatives) are newly established entities with zero experience, no credit history and no proof that their businesses are heading towards profitability. So the risk that they will not be able to pay back their loans is high.”

If a significant number of cooperatives default simultaneously, Media said, “it could shake the stability of the entire banking sector”.

Achmad of Jakarta National Development University echoed the sentiment.

"Not all of these cooperatives will be profitable, certainly not immediately. In the meantime, (the villages) will have to pay (back the loans) in instalments. If they cannot repay then it will be a disaster for these villages and the banks," he said.

For the villages, Achmad added, they might see strategic assets seized by the banks if they defaulted. Meanwhile for the banks, they might face liquidity issues from these non-performing loans.

HIGH RISK INVESTMENT

Analysts also expressed doubts on whether the cooperatives will be well-managed, given the relatively short lead time from its inception to launch, with the Red-White cooperative programme first floated by Prabowo at a Cabinet meeting only in March.

“I doubt the government can find competent people to manage these cooperatives in such a short amount of time,” Achmad said, adding that the short timeframe also leaves little room for the government to come up with proper business models.

“Coming up with a business model that works is not easy. They must be tailored to the specific characteristics of a village, its economic potential and its people. Even then, it takes years to build the solid foundation needed for a cooperative to be profitable and sustainable.”

Experts say the lack of a viable business model and the top-down nature of the programme are reminiscent of Suharto's Village Unit Cooperative (KUD) programme, which was also designed to be multi-functional rural enterprises.

When it was launched in 1973, Suharto made a pledge similar to Prabowo’s that the programme would cut down the middlemen, eradicate the predatory lending practices of loan sharks and ensure subsidised goods would not fall into the wrong hands.

“But because of mismanagement, debts were mounting, loans went unpaid, corruption was rampant,” Acuviarta Kartabi, an economist from Pasundan University, told CNA.

Government support for the 9,000 KUDs established during the Suharto regime ended when he stepped down as president in 1998. Since then, most have declared bankruptcy or have been abandoned by their members and fallen into obscurity. Only 385 are still active today.

“Such is the risk of establishing cooperatives born out of a top-down policy. They become dependent on government incentives and support because they were born not out of people’s needs and initiatives,” Acuviarta said.

Prabowo has promised that his Red-White cooperatives will be closely monitored, preventing cases of embezzlement and corruption.

“Technology will allow (cooperatives) to be monitored closely. All money coming in and out (will be monitored) through technology. (Corruption involving cooperatives) will be a thing of the past,” he said.

Prabowo also said that his programme “will be the backbone of local economies” and that people will do what they can to keep their local cooperatives afloat, with or without support from the central government in Jakarta.

COMPETENT PEOPLE NEEDED

Despite the risks, experts and industry players believe that some of these cooperatives can thrive and have the potential to improve local economies.

“There are farmers who struggle to get bank loans because they do not have bank accounts or because they are not legal entities. The savings and lending services provided by these cooperatives can offer solutions for our members,” Muhlis Wahyudi, secretary-general of the Indonesian Poultry Farmers Association, told CNA.

Muhlis said his association is also hoping these cooperatives would buy chicken meat and eggs from traditional farmers at fair and stable prices.

“Because prices fluctuate, we sometimes have to buy feed when prices are high and sell our chicken when prices are low. Many of our members went bankrupt because of this issue,” he said.

Experts said in order for these cooperatives to work, the government needs to recruit people who have a good understanding of the problems faced by locals in certain areas and turn these problems into economic opportunities.

“Each village has their own unique sets of challenges and opportunities. One village might benefit more from the logistics arm of the cooperative because of how remote it is and (be) less reliant on storage facilities because the products they sell are not so perishable,” Media of CELIOS said.

“Some villages might not even need a new cooperative because they already have one born out of their own initiative that is working and thriving.”

Economist Achmad echoed the sentiment.

“It takes more than the big budget and goodwill of the government to build a cooperative programme. They must be based on people’s needs, run professionally and monitored closely by internal and external mechanisms,” he said.

Acuviarta of Pasundan University said Prabowo should have started small to prove whether his concept actually works.

“Training cooperative officials, monitoring their performance, determining what system and business models work and which don’t, making adjustments and improvements, these all take time,” Acuviarta said.

“There’s no need to rush.”

免責聲明:投資有風險,本文並非投資建議,以上內容不應被視為任何金融產品的購買或出售要約、建議或邀請,作者或其他用戶的任何相關討論、評論或帖子也不應被視為此類內容。本文僅供一般參考,不考慮您的個人投資目標、財務狀況或需求。TTM對信息的準確性和完整性不承擔任何責任或保證,投資者應自行研究並在投資前尋求專業建議。

熱議股票

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10